This poem emphasizes the importance of recognizing that health is an inseparable part of Indigenous culture. It speaks to public health professionals and policymakers, urging them to deeply consider indigenous arts, festivals, and culture when collaborating to create programs and policies for these vulnerable communities. To highlight the importance of improving cultural competence in Indian health systems, it draws inspiration from 'Sarhul,' a spring festival or the festival of flowers, celebrated by many tribes like the Oraon, the Munda, and the Ho of Jharkhand.

The Sarhul festival marks the beginning of spring. During this time, tribal communities offer prayers to the spirits of their ancestors and perform rituals of gratitude toward nature. It is a time to reflect on the past year, express thanks to the spirits for maintaining the world, and pray for a prosperous year ahead.

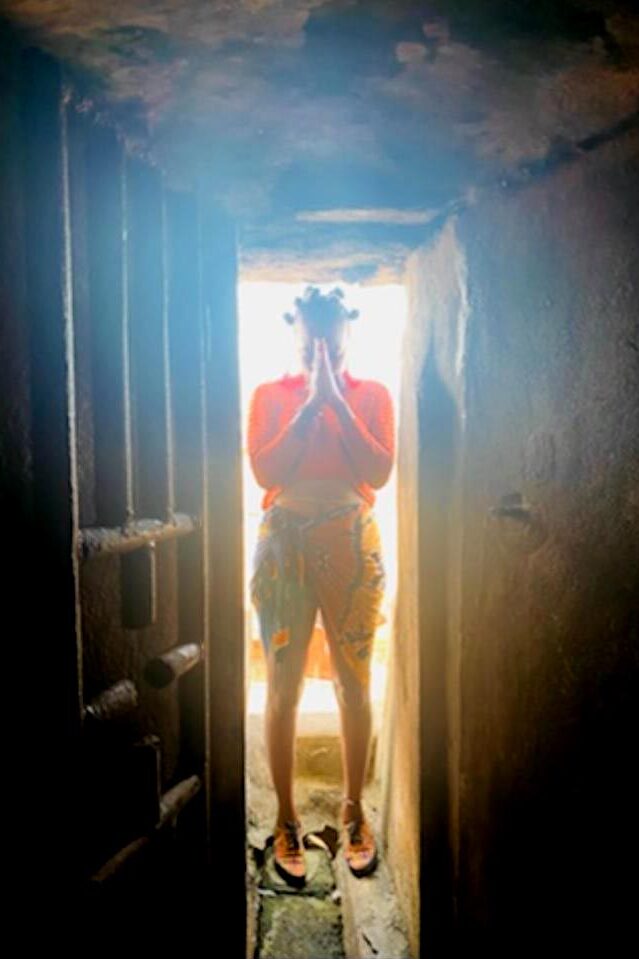

In the photo, tribal communities are performing the Sarhul dance, celebrating with Sal tree flowers (Shorea robusta) tucked behind their ears. Connected in a human chain, they move in circles, dancing to the rhythmic beats of traditional instruments like the dhol and mandars (bifacial drums).

Speaking of Indigenous Health

And how slowly we realise

that health is one of the petals

of the flower of culture.

Predicaments arise

when you look at the two apart.

You can never arrive

in spring with a torn flower.

You never get a boundless picture

if you only memorized public health theories

but have never felt the opulence

of sal flowers tucked

behind your ears on Sarhul.

*Sarhul is an indigenous spring festival in Jharkhand, India.

Europe is currently experiencing the worst energy crisis in global history. Following the onset of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the intersection of physical, behavioral, and economic household-related dimensions of energy has been amplified. Funded by the Kosciuszko Foundation, this project's central question was, “How does the energy crisis impact weathering stressors stemming from the housing and energy continuum?”

A research group of 19 residents in Wrocław, Poland, participated in this Photo Voice study. Utilizing a grounded theory approach, data analysis consisted of triangulating results from survey responses, collected photographs, and recorded semi-structured interviews. The results revealed how the energy crisis influenced life satisfaction, loneliness, social support, health, and well-being. The weaponization of energy by the Russian state emerged as a key theme.

This photo was captured by a 35-year-old Ukrainian male who is a home renter. The participant explained that the Polish government is insufficiently addressing the Russian state’s weaponization of energy. Collectively, participants in the study exhibited feelings of hopelessness due to certain aspects of their daily life being out of their control. The constant stress of not having the capacity to appropriately address energy-related hardships contributes to the weathering of biopsychosocial health and well-being among Polish residents.

By examining participants' lived experiences, this research highlights the energy crisis's impact on public health research and policy. Conducted in southwestern Poland where cold weather and heating issues are significant, these issues are potentially worse in mountainous regions. However, housing conditions across Poland are outdated, impacting structural and technical components. The results of this study inform public health and housing advocates, and contribute to developing measures for addressing weathering stressors among Poland's historically oppressed population.

This study, approved by the University of Wrocław (UW) Ethics Committee, is part of the project "Exploring Aging on the Energy and Housing Continuum in Wrocław, Poland." All participants underwent training and provided written consent. Led by the Centre for Interdisciplinary Research into Health and Illness at the UW, the goal of this art-based research was to promote public health participation, awareness, and inform research and policy.

Contact: paul.mokrzycki@uwr.edu.pl

By Lisa Labita Woodson

Here is an original poem I wrote following a field visit to study sites in Loreto, Peru, along the Marañón River, a major tributary of the Amazon River. My research focused on the downstream impacts of COVID-19 mitigation efforts on adolescent pregnancy in one of the country’s impoverished regions marked by a high rate of adolescent pregnancy and poor maternal and child health indicators. It outlined pathways that connect the risk of adolescent pregnancy to several ecological system factors from the macro, micro, and individual levels such as poverty, lack of education and health care access, and social and gender norms that limited female autonomy and helped to conserve the practice of early unions. In addition, communities faced new challenges posed by the widespread adoption of technology among adolescents amplified during the pandemic. This poem weaves together different lived experiences of young girls in the Amazon synthesized from data collected from interviews and focus group discussions with adolescents, apus or community leaders, and educators, as well as secondary data sources and field observations.

Heavy rain floods through open windows

puddles across the wooden plank floor

traffic worn from chickens and children

impatient for the season’s end

as they wait like islands on the Marañón.

A pregnant girl rests her swollen body

across the warped metal rocker

careful to balance her weight while

pushing her feet firmly onto the ground

and her back to the chair’s spine.

In the dry season, she had played

voley in the open fields before her

that now pool above her waist

threatening to swallow the bodies of girls

too young to carry to term.

In the secret pleasures of the oscura,

he had exposed her with his body’s weight

and used his cell phone to examine her

pubescent breasts before abandoning her

for otro trabajo down the Marañón.

Yet she still waits, days swollen by tears

she does not cry but floods the haul

of the peke peke used to carry her body

upriver to Nauta’s eroded oil-slicked banks

but not time enough to save her

—and her unborn child.

Please note that this is a sample Gallery entry as it has been previously published.

Woodson, L. L. (2023). The Power of Poetry: Rethinking How We Use Language in Global Health Research. American Journal of Public Health, (0), e1-e2. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2023.307495

By Priyanka Ravi

Beedis are hand-rolled smoking tobacco manufactured in India. The process of making beedi includes collecting tendu leaves and tobacco, rolling them into beedis, then sorting, labelling, wrapping, and packing of beedis. Majority of the employees who are responsible for rolling beedis are women. They are paid Rs. 250 to 300 ($3.00 to $3.60 USD) to roll a thousand beedis. In this picture, a beedi roller has wrist pain due to the constant rolling of tendu leaves with tobacco fillers. These workers experience chronic pain in the wrist, upper and lower back, shoulder, and leg as they sit in the same position for long hours. A beedi worker says,

“I use a painkiller or analgesic spray for my pain and tie a cloth after applying the spray to keep my hand warm. That provides some support to my wrist while working.”

These workers practice self-medication or use home remedies to control chronic pain, and some of them continue to work in pain. There is no definite work time, so some of the workers start to work from 1:00 pm to 1:00 am or until they finish 1000 beedis. There is a need for safe health work policies to improve the life of these workers.

Credit: Husna Banu, Beedi workers and community member

Beedis are hand-rolled cigarettes and most used smoking form of tobacco in India. Various health effects of beedi have been reported; however, there is scant evidence on the potential health effects of tobacco on beedi workers. The aim of this project was to explore the experiences and challenges faced by the women beedi workers handling unburnt tobacco using Photovoice, a community-based participatory method. We recruited 20 women involved in beedi rolling for at least a year. One-day training was conducted on principles and ethics of photography, photo consent and safety, field practice using digital cameras, and group discussion and reflection about the photovoice. Participants were then asked to take pictures of what best represents occupational health challenges in their workplace. Photos were taken for four weeks, and after every seven days, the participants discussed the pictures with the research team. The major themes were health problems, alternate employment, occupational constraints, household responsibilities, interpersonal relations, children's health, social inequality, and economic burden. Empowerment measures include thinking about the problem, leadership, facilitation, photography, and presentation skills. Photovoice exhibitions were arranged within the community for community leaders, community members, and policymakers. The project findings provide a better understanding of health and social challenges. Written informed consent and photo release consent have been obtained from the participants.

Photo of the Author, returning to face the “Door of No Return,” located on the Gold coast of Ghana, West Africa where enslaved persons where transported as human cargo and shipped to North America and the Americas.

By Shameka Poetry Thomas, PhD

All I know is that growing up Black-American in North America, I have been socialized and surrounded by whiteness my entire life. Even while graduating with distinguished honors from a historically Black college in Atlanta, Georgia. Even while growing up in Black Miami, attending an African Methodist Episcopal church. Even while returning and living in an African majority space (Ghana), I notice the middle passage within my tongue, my accent, and my brain cells. Whiteness like a thunder, still psychologically present, hegemonic, and consuming. No matter the physical location on this planet, there is no escaping the ramifications that colonialism left behind. That shadow. Everything about my existence becomes questionable because of it: my chocolate skin, my hair, my eyes, my ovaries, my infants, my breath, my jogging through neighborhoods. Even words like “third world” or “developing country” have undertones of neocolonialism, specifically about the “world-order” because it neglects to acknowledge that natural resources are taken from such nations to sustain the global economy of first-world, developed nations. coughing: Europe and / or North America*

Radical self-care, for me, meant returning to the “Door of No Return,” to stand facing-forward. Discovering my inner beauty without the shadow of the white gaze in my mirror, hunting me in my travels or in my writing. Toni Morrisons’ novels holding me at night. Radical self-love also meant refraining from the romanization of continents and populations that has been raped. I had embraced that this journey is not pretty, which makes it so naturally sweet. And for some people, naturally sweet is—bitter: Aloe Vera, tea oil, cayenne pepper.

A beautiful voyage into chocolate. Could that ever be possible without it being sci-fi? Could I write about what it means to be psychologically independent from oppression? Could I experience the gorgeousness of human life across the African Diaspora and call it pleasure, beyond it being seen as “dirty” and “exotic”? Could this narrative be seen as sacred and holy, as it is? Meaning, could I call myself a traveler without Europe or Europe’s hand in my pocket? Do I even know what that means? Would my audience even know what that means? Could I be that free? I do not know.

What I do know is:

Ultimately, when I say the African Diaspora, I do not necessarily mean only visiting countries of the transatlantic slave trade or “middle passage,” or between West Africa and the Americas. Every city on this planet was severely impacted by the transatlantic slave trade. There were also countries that were impacted by colonialism, beyond being a direct portal of human cargo. I am particularly curious, however, about what it means to see and perceive my own lived experiences (in my own chocolate skin), in any country where I can allow myself to tap into the metaphysical realm of my inner voyage as true self-discovery and political pleasure.

Can I stand in this “door of no return” and give honor to grandmothers whose names I will never know? Names stolen; bodies raped. Can I stand in this doorway and cry by myself? Can I allow myself to be upheld by invisible ancestors who whisper affirmations and drums to soothe my heart, as a long lost granddaughter returning? Can I not speak in English? Can I not think like an American? Can I step outside my socialization? Can I put my hair in Bantu knots and wear waist beads and be seen as goddess and glory?

By Tina Samsamshariat

These images and accompanying narratives are provided by agentes comunitarios de salud (ACS) or community health workers with the Mamás del Río project, sharing their personal experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Peruvian Amazon. These photographs were captured as part of my Global Health Equity Scholar/Fogarty research which examined how community health workers expanded their roles to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 pandemic within their communities. Informed consent and photo release consent were obtained from all study participants to share their photos.

"This little box is a community medicine cabinet. In the community, it is the responsibility of the health promoter, and it is mainly for the benefit of the community. As an agent, I feel worried because it is empty. It is like a soldier who goes to war without weapons. You are left with great despair at not being able to provide support. The disease comes and we do not make it alive."

"Our role is not only to treat the patient, it is to support him so that he can reach the health post. Therefore, we must promote communal medicine cabinets with higher authorities. We want training on medicine administration, so that we can be prepared for an emergency in our community."

- ACS

"A community health agent is visiting a community member with COVID-19 in the middle of the pandemic. At first I was afraid, but at that time, I would always check on [the patients] to see how they were, if they were getting better, if they were getting worse–that was my job. My will is great. I don't earn a penny; you don't earn any incentive, but I work for my community. There was a danger that some community members would die from COVID-19. For that reason, I had to worry. If they leave [their house] to go visit their neighbor, they will infect them. Thus, in order to avoid that, since I had protection, I would leave."

-ACS

"I was no longer afraid of death. I supported our patients by preparing their herbal remedies. We can teach our community members to prepare the remedies, and give it to them to drink, so that our community does not fall so hard in the pandemic."

Please note that this is a sample Gallery entry as it has been previously published.

Samsamshariat T, Madhivanan P, Reyes Fernández Prada A, Moya EM, Meza G, Reinders S, Blas MM. Hear my voice: understanding how community health workers in the Peruvian Amazon expanded their roles to mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic through community-based participatory research. BMJ Glob Health. 2023 Oct;8(10):e012727. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2023-012727. PMID: 37832965; PMCID: PMC10583076.

By Adriana Garcia Saldivar

In January 2023 there were a series of protests in Peru against the government of Dina Boluarte, happening with more force in the southern regions. In Juliaca (Puno) state forces victimized 18 people, many of them young people, in a display of racism and abuse of power. This city is characterized by having a very cold climate, its streets are mostly not paved, drinking water and sanitation services are needed; and like many areas of Peru, they lack quality basic services. In this context, a young woman was giving birth during a massacre, having to face the precariousness of the health service, obstetric violence and state terrorism.

The poem begins from the perspective of the researcher who is in charge of a focus group of young women in Juliaca, applying this methodology as part of an investigation to understand subjective well-being. Throughout the poem the researcher narrates her own reflections from beginning to end, describing what she hears and observes, the changes in herself and in the group, all while they eat lunch in an increasingly welcoming and safe space.

Las chicas saltan las bolsas de basura,

se sacuden del frio y de los muros altisonantes,

de cada esquina y de sus vueltas sin asfaltar.

Adentro, pasen

Si abro la ventana huele a gas lacrimógeno, todavía,

y huele a leche, yogurt y shampoo.

Ellas van formando un cerco,

apretadas y bajitas,

ellas y Juliaca

como un cintillo apretando,

sí, es un cerco humano,

sí hay café, si hay

Una cabecita sin pelos, una mandarina,

voltea y babea sobre su madre

Ah, la leche y el shampoo,

sostengo y paso,

me siento y trago

Juliaca 2023

Ella me dijo que cargaba a dos,

no un herido,

pero si iba a cuestas y sangrando,

subiendo y bajando

entre gases, casquilllos y miedo,

ella también marchaba

Todas las rutas para llegar al hospital

y toda la gente corriendo hacia allá,

apretando el mar humano, asfixiando.

Entre el ácido no hay sala de parto,

pero le brotó del pecho y del vientre

rojos y blancos, respirando.

Sin paro es lo mismo dice

igual los gritos, igual te hacen llorar

Borboteamos

...

La misma ciudad,

de calma tétrica,

de bullicio alarmante,

de un silencio inquietante,

El paro, el paro, el parto

Esa noche, todos murieron esa noche,

pero aquí están,

la mandarina y el shampoo,

la leche y el yogurt

El cerco es más cálido y pequeño, todas se pegan más,

se trenzan los brazos, el cuerpo

Juliaca 2023

y una ronda más de café.

This is a sample Gallery entry as it is waiting to be translated in English. An updated version will be available at a later date.

©2024. Made with (❤︎) in Yachayninchik